http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/01/us/01citrus.html

Deep Roots, Sweet Oranges and a Taste of Floridas Past

By DAMIEN CAVE

Published: December 31, 2009

Silvia Gamez sorted through citrus at Als Family Farm in Fort Pierce, Fla.

Silvia Gamez sorted through citrus at Als Family Farm in Fort Pierce, Fla.

Josh Ritchie for The New York Times

Jeffrey Schorner darts through Als Family Farms like a car salesman in a crowded showroom. He brags about his orange juice. He climbs under the packing machine. He grabs a tangelo for a gift box, then orders his 15-year-old son to the nearby groves.

Pick me two sunbursts, he shouts, sounding like his own father, Al, who founded the company. Then pick lemons.

Before Interstate 95, Starbucks and Sbarro, roadside citrus stands like Als lined nearly every major thoroughfare in Florida. They made buying local fun before the locavore food movement made it fashionable, but increasingly they are a dying breed.

Hundreds if not thousands of family citrus farms and their roadside stands have disappeared since the 1960s victims of freezes and disease, highways that diverted customers, corporate consolidation, and the relentless pressure on growers to sell their land to developers. Since 1996, Florida has lost more than 200,000 acres of citrus land, according to state figures, mainly to homes that no longer sell like the oranges they replaced.

Only here, in the 90-mile bluff along the Indian River from Cocoa to Fort Pierce, can one find the last handful of citrus stores that offer the stickiness and tart scent that once defined the state.

The land gets part of the credit. It has been famous since 1835, when Douglas Dummetts plantation on Merritt Island survived a brutal freeze thanks to the nearby rivers that stabilized temperatures. Dummett also bred sweeter fruit after the Civil War, his oranges commanded $1 more a box in New York than oranges from any other grove and Indian River went on to become one of Floridas most famous farming brands.

Northerners like Roy and Blanche Harvey, who arrived in the area from Cleveland in the 20s, could hardly resist. Larry Harvey, their grand-nephew, said their family business started when Blanche picked a few oranges and started selling them on U.S. 1., then the main road running north and south. Now, at essentially the same location in Rockledge,

Harveys Groves is the last citrus shop around.

Like most of its counterparts farther south, the store has a homeyness that comes from its white-painted barn and bins of fruit, its kitschy extras (turtle earrings, anyone?) and from employees who have worked there for more than 20 years.

Harveys displays braggadocio, too. The giant orange in the green elfin costume on the roof and the large sign boasting of the worlds best orange juice might as well be museum pieces for Florida hucksterism. Although Mr. Harvey, 64, refuses to admit it. A leukemia survivor with a bushy mustache, he is the softer side of a management team that includes his brother, Jim. Worlds best is accurate, Larry Harvey insists, and as proof he showed off his shiny FMC extractor, a stainless steel juice machine that resembles a truck engine attached to rubber straws.

He said three types of oranges go in: tangerines, tangelos and golds. What pours out tastes fresher than what is in the average supermarket carton, he said, because of the blend, and the lack of pasteurization. This is superchilled, he said. It doesnt have the shelf life, but it tastes better.

Juice, it seems, is where the roadside stands still like to compete. Dixie cups of the stuff are handed out to all who enter at Als and Harveys. At

Hale Groves on U.S. 1 in Wabasso, the sign out front offered all you can drink for 10 cents in 1951, but now it says the freshest and best tasting. Guaranteed since 1947.

Still, with a smirk, owners like Mr. Schorner acknowledge that the juice is half vanity project, half marketing gimmick. Even the stands are merely showplaces, as John McPhee wrote in Oranges,

his book from 1967, because the bulk of the business comes from shipping gift boxes north.

This accounts for 80 percent of Harveys sales. Its a similar proportion for the others. Basically, without orders placed through the stores, catalogues or the Internet, all these companies would be out of business.

Holiday gifts matter most of all, and this year, sales are up. According to the Florida Gift Fruit Shippers Association, volume increased by 1.75 percent this season.

Not that there are any hallelujahs around Indian River. The growers sell optimism, but sleep with fear. Mr. Harvey said there were 152 members of the

Gift Fruit Shippers Association when his father helped start it in the late 40s. Now there are 37.

Meanwhile, the famous Indian River citrus region has come to look a little more like the rest of Florida in recession. Driving U.S. 1 now offers views of a closed packing house named Victory, silent strip malls offering three months free rent, and at least one development with empty lots where groves used to be and where new homes may never rise.

Economic ups and downs, of course, are not unfamiliar to the roadside citrus crowd. And the bust has brought a bonus: Mr. Schorner said a few former growers are returning to citrus after failing at real estate.

But if you ask the older owners what will happen next with their businesses, or how they have survived, you are likely to get a humble shrug. Its my charm, said Ed Peterson, 73, whose family has been selling oranges from

its grove in Vero Beach since 1923.

No, said his brother and co-owner, Fred, 70, standing behind the counter in red shorts faded pink. Weve worked hard; thats what it is. Weve refused to give up.

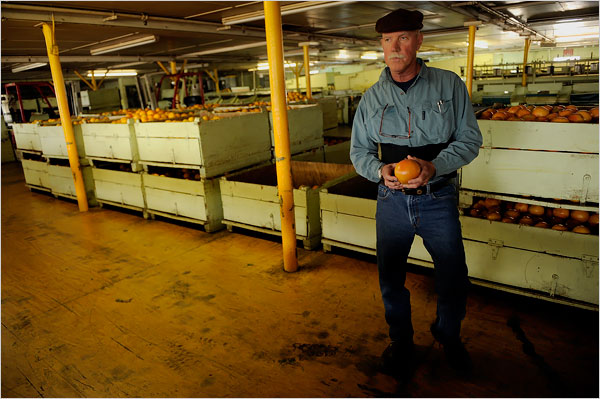

Al's Family Farms along Kings Highway in Fort Pierce, Fla. The business, which began as a citrus

Al's Family Farms along Kings Highway in Fort Pierce, Fla. The business, which began as a citrus

packing plant, became a citrus stand 32 years ago.

Photo: Josh Ritchie for The New York Times

Before major highways like Interstate 95 were built, roadside citrus stands like Al's lined nearly every

Before major highways like Interstate 95 were built, roadside citrus stands like Al's lined nearly every

major road in Florida. They made buying local fun before the locavore food movement made it fashionable.

Now they are increasingly a dying breed.

Photo: Josh Ritchie for The New York Times

Marmalade is among the treats sold at Al's. The business also sells locally grown citrus as well as honey,

Marmalade is among the treats sold at Al's. The business also sells locally grown citrus as well as honey,

tomatoes, nuts and juices.

Photo: Josh Ritchie for The New York Times

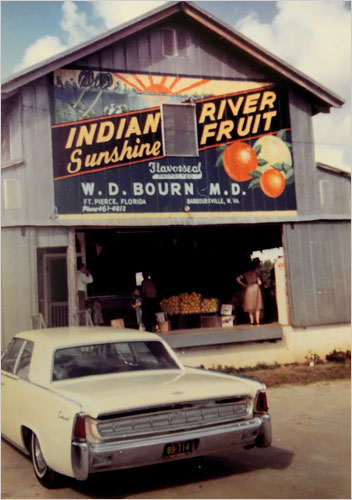

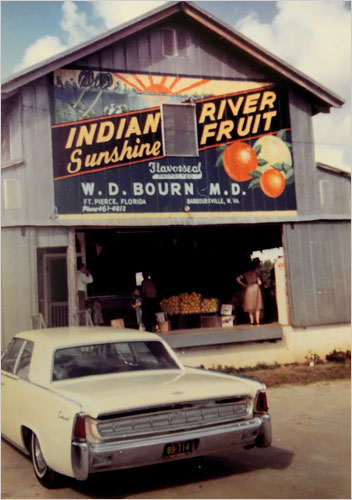

When Al's was still a citrus packing plant in the 1950s, it

When Al's was still a citrus packing plant in the 1950s, it

was named Indian River Sunshine Fruit. The land in the

area has been famous since 1835, when a plantation

survived a brutal freeze because of nearby rivers that

stabilized temperatures.

Photo: Josh Ritchie for The New York Times

W.D. Bourne, the founder of Indian River

W.D. Bourne, the founder of Indian River

Sunshine Fruit, which later became Al's Family

Farms.

Photo: Josh Ritchie for The New York Times

Felicitas Gamez sorting fruit at Al's. At some farms, gift boxes of fruit sent north account for 80

Felicitas Gamez sorting fruit at Al's. At some farms, gift boxes of fruit sent north account for 80

percent of the sales.

Photo: Josh Ritchie for The New York Times

Holiday sales were up this year for citrus in the state. According to the Florida Gift Fruit Shippers

Holiday sales were up this year for citrus in the state. According to the Florida Gift Fruit Shippers

Association, the volume of gift sales increased by 1.75 percent this season.

Photo: Josh Ritchie for The New York Times

Maria Lopez working on the boxing line at Al's.

Maria Lopez working on the boxing line at Al's.

Photo: Josh Ritchie for The New York Times

Ups and downs are familiar to the roadside citrus crowd. After the real estate bust, the famous citrus

Ups and downs are familiar to the roadside citrus crowd. After the real estate bust, the famous citrus

region has come to look more like the rest of Florida in recession. Still, some former growers are

returning to citrus after having failed at real estate.

Photo: Josh Ritchie for The New York Times

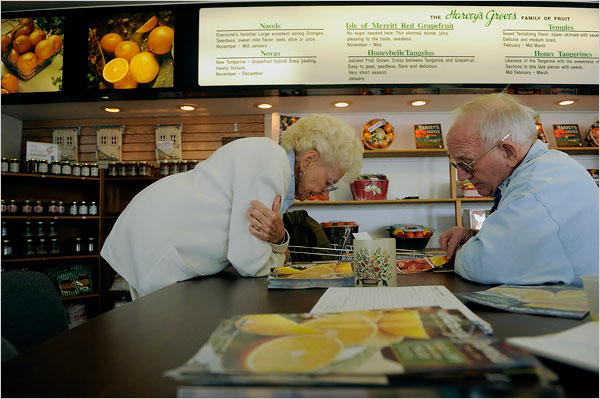

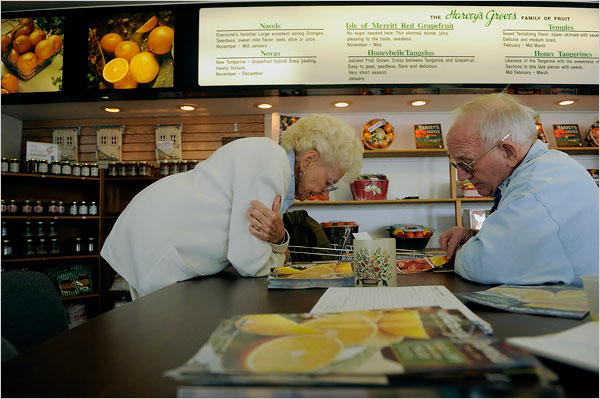

Customers at Harvey's Groves in Rockledge. The owners said that the business began in the 1920s

Customers at Harvey's Groves in Rockledge. The owners said that the business began in the 1920s

when Blanche Harvey picked a few oranges and started selling them on U.S. 1., then the main road

running north and south.

Photo: Josh Ritchie for The New York Times

Like most of its counterparts, Harvey's has a homeyness that comes from its

Like most of its counterparts, Harvey's has a homeyness that comes from its

white-painted barn, its bins of fruit and from its long-term employees.

Photo: Josh Ritchie for The New York Times

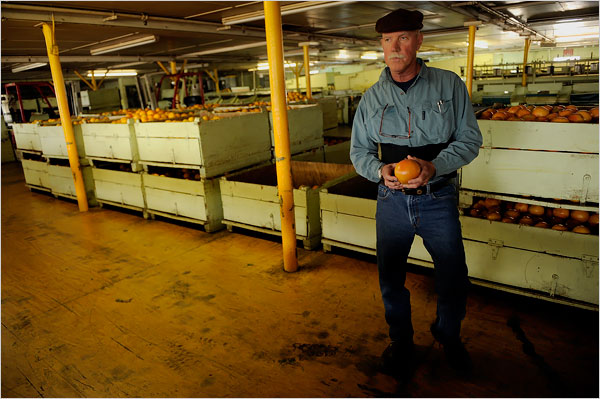

Larry Harvey, 64, said that his juice blends are fresher than the average than what's inside the average

Larry Harvey, 64, said that his juice blends are fresher than the average than what's inside the average

supermarket carton, despite the weaker shelf life of unpasteurized juice. Juice has been where roadside stands

have competed historically. At Harvey's, all who enter are handed cups of juice.

Photo: Josh Ritchie for The New York Times

John Clayton and his wife, Ellie, looking over their ordering options at Harvey's. Sales for many growers

John Clayton and his wife, Ellie, looking over their ordering options at Harvey's. Sales for many growers

have increased this year in part by the lifting of a federal ban on shipping to other citrus-producing states to

prevent the spread of canker.

Photo: Josh Ritchie for The New York Times