http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601170&refer=home&sid=ayj1uo_gdNI4

It should be good news. Dakota doesn't seem to belong in the No Drilling Zone:

But before we jump up and down in this report, take note that , others have commented the following:

US daily oil consumption - 21 million barrels

US yearly oil consumption - 7.6 billion barrels.

Worldwide yearly consumption - 31 billion barrels.

Add ANWR (10.4 billion barrels) and Bakken (4.6 billion barrels): This totals just about 2 years of US consumption.

About Saudi production and reserves, the last Saudi reserve estimate completed while US geologists were involved was 110 billion barrels in 1979, with a slight chance it could be as high as 168 Giga barrels)

Saudi production to date 81 billion barrels, implying 29 to 87 Gb remaining; Saudi claims 264 Gb remaining (a highly suspect claim, as OPEC rules for production limits encourage overestimating reserves)

Russia's production is in the decline

Indonesia became a net oil importer.

Mexico and Venezuela down in production.

There's a lot of uncertainties...

Joe

"That Saudi Arabia has about 260 billion in provable reserves. 50 of which they have already pumped. I though it was interesting in 2 respects. One that this Bakken reserve is estimated between 100 billion and 600 billion and 2 that after all this time Saudi Arabia has only pumped 50 billion so far. Does a lot to dissuade peak oil."

Dakota Oil Fields of Saudi-Sized Reserves Make Farmers Drillers

By Anthony Effinger

June 3 (Bloomberg) -- John Bartelson, who smokes Marlboro Lights through fingers blackened with tractor grease, may look like an average wheat farmer. He isn't. He's one of North Dakota's new oil barons.

Every month, he gets a check for tens of thousands of dollars from a company in Houston called EOG Resources Inc., which drilled two oil wells on his land last year. He says the day his first royalty check arrived was one to remember.

``I smiled to beat hell, and I went to town and had a beer,'' Bartelson, 65, says.

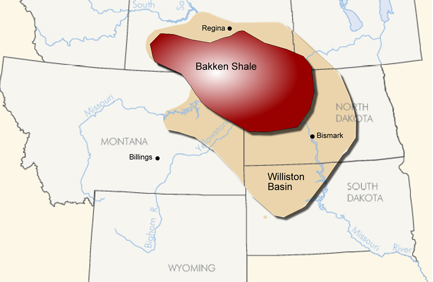

His new wealth springs from the Bakken formation, a sprawling deposit of high-quality crude beneath the durum wheat fields of North Dakota, Montana and southern Saskatchewan and Manitoba. The Bakken may give the U.S. -- the world's biggest importer of oil -- a new domestic energy source at a time when demand from China and India is ratcheting up the global competition for supplies and propelling average U.S. gasoline prices to almost $4 a gallon.

And unlike the tar from Canada's oil sands, Bakken crude needs little refining. Swirl some of it in a Mason jar and it leaves a thin, honey-colored film along the sides. It's light - -almost like gasoline -- and sweet, meaning it's low in sulfur.

Best of all, the Bakken could be huge. The U.S. Geological Survey's Leigh Price, a Denver geochemist who died of a heart attack in 2000, estimated that the Bakken might hold a whopping 413 billion barrels. If so, it would dwarf Saudi Arabia's Ghawar, the world's biggest field, which has produced about 55 billion barrels.

Thin Deposit

The challenge is getting the oil out. Bakken crude is locked 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) underground in a layer of dolomite, a dense mineral that doesn't surrender oil the way more-porous limestone does. The dolomite band is narrow, too, averaging just 22 feet (7 meters) in North Dakota.

The USGS said in April that the Bakken holds as much as 4.3 billion barrels that can be recovered using today's engineering techniques. That's a fraction of the oil that Price said should be there, but it's still the largest accumulation of crude in the 48 contiguous U.S. states. North Dakota, where Bakken exploration is most intense now, won't become Saudi Arabia unless technology improves.

``The Bakken is the biggest thing in oil in the lower 48 right now,'' says Jim Jarrell, president of Ross Smith Energy Group Ltd., a research firm in Calgary. ``And among the least understood.''

Delaying the Peak

Some oil, like the 10.4 billion barrels estimated to be recoverable in Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, remains off limits -- as a nature conservation measure -- even as President George W. Bush renews his calls for drilling there. North Dakota, already crisscrossed by farm roads, is open for business.

As traditional oil fields become scarce, exploration companies must tackle trickier ones to stay in business. Their success will determine when the world reaches peak oil -- the high point in production after which new supply will no longer be there to slake new demand. It's a gloomy concept. Peak oil theorists predict the mother of all oil shocks, complete with famine and wars for energy.

These days, big new oil deposits often come with caveats. Brazil's Petroleo Brasileiro SA says its offshore Tupi field contains as much as 8 billion barrels of oil, which the company hopes to start pumping next year. But the field is under more than four miles of water and rock, where pressure can crush drilling equipment.

Hedge Bus

The Bakken dolomite is hardly an obstacle, by comparison. And even if Price was too optimistic, the Bakken is big enough to make investors rich. Some have made fortunes already.

In April, a busload of hedge fund managers drove by Bartelson's land, ogling the metronomic pump jacks and the devilish orange flares of excess natural gas that are making parts of North Dakota look more like west Texas.

``There's nothing that can stop this play,'' says Mike Reger, chief executive officer of Northern Oil & Gas Inc., a five-person company near Minneapolis that has leased the mineral rights under 32,000 acres (13,000 hectares) in the North Dakota Bakken.

Reger, 32, brought the hedge fund managers up to see the oil field. Some, like Ryan Zorn of Houston-based investment management firm Saracen Energy Advisors LP, are investors in Northern already. Northern shares have risen 61 percent since being listed on the American Stock Exchange on March 26.

Fool's Gold

For decades, the Bakken was the fool's gold of the oil industry. The name describes a geological formation that looks like an Oreo cookie: two layers of black shale that bleed oil into the middle layer of dolomite. It's named after Henry O. Bakken, the North Dakota farmer who owned the land where the first drilling rig revealed the shale layers in the 1950s.

All of the layers are thin -- about 150 feet altogether -- and none of them give up oil easily. In older, vertical wells, oil would often flow for a month and then fizzle.

Now, companies like Austin, Texas-based Brigham Exploration Co.; Denver-based Whiting Petroleum Corp.; and EOG are drilling horizontally. They go straight down 10,000 feet and then put a slight angle in the mud motor, a 30-foot piece of tubing that drives the bit, so they hit the Bakken sideways, making a horizontal tunnel 4,500 feet long through the dolomite.

That exposes more of the oil-bearing rock. Then they pump pressurized water and sand into the hole to fracture the dolomite, making cracks for oil to seep through.

It eventually winds up in a pipeline that runs east to Clearbrook, Minnesota, and then south to Chicago.

Where Billionaires Roam

Several billionaires are at work in the Bakken. Harold Hamm's Enid, Oklahoma-based Continental Resources Inc. has leases on 487,000 acres in Montana and North Dakota. Hamm, who started out driving a truck, owns 73 percent of Continental, worth $7.9 billion. Philip Anschutz, 68, founder of Qwest Communications International Inc. and Regal Entertainment Group, is there, too.

So are two sons of billionaire H.L. Hunt, the 1930s wildcatter. Petro-Hunt LLC is owned by the trust estate of William Herbert Hunt, who was convicted in a civil trial with his brothers Lamar and Nelson Bunker of trying to corner the silver market in 1979. Hunt Oil Co., another Bakken operator, is owned by their half brother, Ray L. Hunt.

The big winner so far has been EOG, formerly a subsidiary of bankrupt energy trader Enron Corp. It drilled a horizontal well in western North Dakota just north of Parshall -- population 1,028 -- in April 2006. The well came online a month later and kicked out 1,883 barrels in the first seven days. Unlike the older vertical wells, it's still going. In March, it produced 2,305 barrels, according to the North Dakota Industrial Commission.

No Slam Dunk

EOG has eight rigs running on 320,000 acres of mineral leases in the North Dakota Bakken. The company said in its 2007 annual report that the area has the highest return of all the places in which it operates -- including Texas's Barnett Shale, the Gulf of Mexico coast and the Permian Basin of New Mexico.

The Bakken isn't foolproof. Far from it. Drilling there is expensive -- about $5 million a well, according to EOG -- and takes experience. Dallas-based Petro-Hunt's first well in the North Dakota Bakken didn't make money, company geologist Steve Bressler says. Brigham's Bergstrom Family Trust well came online at 277 barrels a day -- viable at today's high oil prices but not a gusher.

``There will be variances,'' says John Gerdes, an oil and gas analyst at SunTrust Robinson Humphrey Inc. in Houston. ``The rock matters. The people matter.''

Oil Rush

The success of EOG's Parshall well set off a land grab in North Dakota's Mountrail County. Land men -- the experts who move from boom to boom leasing mineral rights -- swarmed, paying ever higher prices for ground that for decades grew crops and concealed Cold War missile silos.

On private acreage, land men negotiate with mineral owners like Bartelson. They offer a bonus upfront to hold the mineral rights for three to five years, and they agree to pay a fraction of the revenue from any oil produced each month -- often from 1/8 to 3/16. On land with a producing well, the mineral lease lasts as long as the well does. On government land, the bonus is set at auction.

Bartelson in 2004 granted a five-year lease on 1,400 acres, under which he owns half the mineral rights. He got a bonus of $25 per mineral acre, or $17,500, plus one-sixth of any oil revenue. Times have changed since then. In November, Sinclair Oil Corp. of Salt Lake City paid $16,500 an acre at auction for half the mineral rights on 320 acres of government- owned land in the Parshall Field, according to the U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

`No Acreage'

``That's a record for Montana and North Dakota,'' BLM spokesman Greg Albright says.

Among the biggest companies punching holes in the North Dakota Bakken are Houston-based Marathon Oil Corp., the fourth- largest U.S. oil company, and Hess Corp. of New York, which is No. 5. No. 1 Exxon Mobil Corp. isn't active in the Bakken. John Freeman, an analyst at investment bank Raymond James & Associates Inc. in Houston, says Exxon is looking for bigger deposits overseas.

``Now, there's no acreage left,'' he says.

The truest believer in the Bakken might be Reger, the CEO of Northern Oil. He's certainly the loudest promoter.

Reger is a fourth-generation oilman. His great-grandfather managed operations for Mobil Oil, now part of Exxon Mobil, in the Williston Basin, the 110,000-square-mile (285,000-square- kilometer) geological formation in the northern plains that holds the Bakken and other deposits. Reger's grandfather leased land atop all of them. His father, uncle and brother are in the business, too.

``It's our basin,'' Reger says.

Bakken Hunters

If it works out the way Reger says, he and his partner, a former derivatives trader named Ryan Gilbertson, will be the Sergey Brin and Larry Page of the Bakken. Like the Google Inc. founders, Reger and Gilbertson are young -- Gilbertson is also 32 -- and they aren't afraid to roll the dice.

The lanky, blue-eyed Reger wears cowboy boots and a saucer-sized belt buckle emblazoned with an ``R.'' He vacationed this year in the Maldives in the Indian Ocean and insisted on a stopover to see Dubai's building boom. Gilbertson, meantime, shot a 10-foot-tall brown bear at eight paces in Alaska in 2007. He has a picture of him and the dead bear on the wall in his office.

`Son o' Bitches'

The future partners met while boating on Lake Minnetonka, outside Minneapolis. Gilbertson is from the area and traded derivatives for Piper Jaffray Cos. and a hedge fund firm named Telluride Asset Management LLC in nearby Wayzata, where Northern is based. Reger moved from Montana to St. Paul to attend the University of St. Thomas.

``We're both cowboy-boot-wearing, country-music-listening, gun-toting sons o' bitches,'' Gilbertson says. These days, they both drive black Cadillac Escalade SUVs and wear designer jeans.

Gilbertson says he knows more about interest-only mortgage bonds than he does about oil. But he says Northern will succeed because he and Reger weren't in business during the busts of earlier decades, so they aren't gun-shy today.

When EOG hit oil, they leased as many mineral rights in Mountrail County as they could, even as prices rose.

``The fear of these busts has clouded the judgment of so many players,'' Gilbertson says. ``We just grabbed everything with both hands.''

Turning Over Leases

Northern makes money without actually drilling or operating wells. Its strategy is like the game of Monopoly: lease in promising areas and get paid when someone else uses the land to drill.

The strategy is possible because of the way land is assembled for drilling. Reger's grandfather, uncle and father had made their money as lease brokers: They'd lease the land themselves or buy leases already granted and then sell them at higher prices to exploration companies.

Reger and Gilbertson intend to keep their leases, pay a share of the drilling costs and keep a portion of the oil revenue. Gilbertson says it was his idea. ``I saw the family's model as flawed,'' he says.

Leasing mineral rights means finding mineral owners. That's not always easy, because the farmer who owns the surface may not own the ``minerals,'' as they're known. Farmers can sell land and retain the minerals. When a mineral owner dies, the rights are often passed in equal portions to his or her children, Reger says, making them hard to track down.

Hauling County Records

To find mineral owners in Mountrail County, land men spend months in the courthouse, poring over photo-album-sized books that show who owns mineral rights and whether they've been leased.

One day in April, there were 50 people lugging books around. They line up well before the courthouse opens to get a spot on the first floor so they don't have to haul volumes up the stairs to an old law library that's been filled with folding tables to accommodate the horde.

Reger started leasing land for oil and gas exploration in Montana at age 15. He carried a portable typewriter to bang out contracts on landowners' kitchen tables.

It takes more than mineral rights to drill. Most western states are divided into neat little squares called sections. Each is one square mile, or 640 acres. If you want to drill an oil well in a section, you lease the mineral rights inside it. You don't need all of them, but you have to find all of the rights owners in that section and offer to let them participate.

This is where Northern makes its money.

Watching Permits

Reger's favorite time of day is 4 p.m., when the North Dakota Industrial Commission posts the names of companies that have gotten permits to drill. Very often, a rig is heading to a section in which Northern has mineral rights. He knows then that it will be a matter of time before he gets a letter from the company asking if he wants to share the cost -- and the revenue -- based on the percentage of mineral rights Northern controls in that section. He almost always says yes.

Reger makes it look easy because the Bakken is hot, says Summerfield ``Sam'' Baldridge, a partner at Montana Oil & Gas Properties Inc., founded by Reger's uncle, Steve, in Billings, Montana. Bigger companies are eager to drill, their wells are producing and oil prices are high.

``If it goes bad, you can go broke really quick,'' Baldridge says. ``You have to have guts and capital.''

Booms and Busts

Baldridge, 51, knows from experience. He was leasing mineral rights for Mobil in Montana in February 1986 when he heard on the radio that oil prices had plunged. In two days, a barrel of West Texas Intermediate crude fell to $15 from $20.

``We knew it was history,'' Baldridge says. ``From Calgary to Houston, everything went south.''

North Dakota has seen booms and busts from an array of oil deposits. The Bakken began forming 360 million years ago from dead algae that sank to the bottom of an ancient sea, where they were buried by successive layers of rock. Heat and pressure turned the algae into oil-saturated shale. Now it lies like a buried blanket under much of the Williston Basin.

Amerada Petroleum Corp. roughnecks started drilling what would become the first well in North Dakota on Sept. 3, 1950. They went through the Bakken before producing oil from deeper Silurian dolomite on April 4, 1951. A year later, Amerada (now Hess) finished the Henry O. Bakken well. Cuttings from the hole showed the shale layers that are now known by the same name.

Finding Porosity

Exploration in the Williston Basin grew for a few decades after that, ebbing and flowing with the price of oil. Mostly, drillers pursued deposits deeper than the Bakken. Those who tried to exploit it usually failed. The oil wouldn't keep flowing. ``Bakken was a four-letter word,'' says Dick Findley, a geologist in Billings.

In 1996, Findley, now 56, had a revelation. The consultant-turned-oilman went out to his rig in eastern Montana one night to check on things. At 2 a.m., it hit the Bakken dolomite and produced an unexpected rush of oil. Oil expands as it forms, and the pressure drives it into rock fractures. In the past, the dolomite hadn't seemed porous enough or fractured enough to release it.

``We got porosity that I didn't know existed,'' Findley says.

Findley and his partner, a land man named Bob Robinson, thought they could re-enter old wells and blast the middle dolomite layer with pressurized water to make cracks for crude to flow. They produced oil but not enough. So they turned to horizontal drilling. The technique had been around for decades.

500 Wells

Some had tried horizontal drilling in the Bakken in the early 1990s. They had aimed for the upper shale layer, though. Findley thought they could produce more by staying in the middle dolomite, even though the best, most porous rock was just 10 feet thick.

They drilled their first horizontal well in May 2000, blasted it with water, and the oil flowed. The field is called Elm Coulee, and today there are more than 500 wells there. Findley sold much of his interest to investors who could afford the drilling, though he still has an override -- a small percentage of any production.

Findley's success got others thinking about the Bakken. One was Michael Johnson, an independent geologist in Denver. Montana and North Dakota require companies to make public the information they collect when drilling, including gamma ray logs, which register the location of oil-bearing shale. Johnson examined logs from hundreds of wells east of Elm Coulee. He zeroed in on a dry one in Mountrail County that had similarities.

Word of Mouth

Johnson and two partners, land man Henry Gordon and geologist Robert Berry, leased about 38,000 acres in the area and shopped the mineral rights around. EOG bought 75 percent across all of the acres. In April 2006, EOG started drilling near a stream called Shell Creek. Workers drilled down some 9,000 feet and then started angling into the Bakken. They hit natural gas and crude.

Oil companies try to keep discoveries quiet so they can snap up more leases around them. Information travels fast in the Williston, though, where all of the roughnecks and rig operators know one another. Reger and Gilbertson had just formed Northern Oil when they got word from a lawyer in Montana that EOG had hit a big one. Reger sent his brother J.R. to lease as much land as he could, as close as he could, to EOG.

Pathfinder

In April, Reger took his busload of hedge fund managers to a well called Pathfinder being drilled by Slawson Exploration Co. out of Wichita, Kansas. Northern owns only 3 percent of Pathfinder but has land all around it. Success here would almost certainly mean more drilling in adjacent sections.

``From this location, we are literally masters of all we survey,'' Reger says.

The drill had hit the Bakken layer two weeks earlier, on Easter Sunday, producing a burst of natural gas. Where there's gas, there's often oil. As the rig clanks and groans like a motorized Godzilla, the hedge fund managers gather inside the trailer and crowd around the desk of Jon Starkweather, a ``mud logger'' who analyzes the rock chips coming up the hole. His window is covered with long charts that look like electrocardiograms.

``We landed this one just right,'' the bearded Starkweather says. Recent gas ventings, called kicks, confirm it.

Even if Reger and Gilbertson stopped gathering more mineral leases, they would make a fortune on what they have already, Reger says.

``I could take a nap for two years under my desk and wake up a hero,'' he says.

Millionaires

Reger's 14 percent stake in Northern is worth about $49 million. Gilbertson has shares worth $24 million. Whiting Petroleum's shares have more than doubled in the past 12 months, triple the 34 percent gain for a group of 96 energy companies in the Russell 2000 Index.

The other people doing well in the Bakken are the mineral owners under the oil wells -- folks like John Bartelson. Whiting paid them $56 million in 2007. EOG declines to say what it paid, though it's certainly more because it operates more wells. Whiting gets much of its Bakken revenue from shares of EOG wells it owns. It acquired them by buying Robert Berry's remaining stake in the Parshall acreage after EOG struck oil.

Bartelson's checks are about to get bigger. One more EOG well just came online, he says, and another is about to be fractured with water. Still another has been permitted for drilling. For now, he's farming. The oil market is fickle, he says. Previous crashes drove the rigs out of North Dakota for years, leaving only the wheat.

``It'll crash again,'' Bartelson says, sipping on a late- afternoon cup of coffee beside his tractor.

Maybe so. But with crude trading above $125 a barrel, it'll be a long time before the rigs leave again, and John Bartelson is likely to be a wealthy man before they do.

To contact the reporter on this story: Anthony Effinger in Portland, Oregon, at

aeffinger@bloomberg.net